Uber’s mobile App

It is fast becoming well known that if you needed a ride home after staying out late, there are two options: 1) An expensive taxi ride if you are lucky to find one or 2) Try out one of these new mobile apps that allows you to summon a car service with a tap of a button.

One of such car service is Uber. Although Uber was launched over 7 years ago, my first ride with them was not until this year’s Sydney Mardi Gras festival when my wife and I struggled to find an empty cab after the parade. It was late and we were both exhausted from standing all night. I decided to try out the Uber mobile app. After entering my personal details and credit card information, the app identified my location and swiftly located the Uber cars around the area and gave me an estimated price. I tabbed a button, and within minutes, a BMW 1-series car pulled up asking for my name.

Less than 15 minutes we were safely back at home. The service was efficient and courteous. As a new customer, this ride was even free! Otherwise it would have been $28.

I was pleasantly surprised and curious to know more about Uber. How does their pricing work? Who is their target customer? And will this be profitable and sustainable way to price for years to come?

What is Uber pricing strategy?

According to the article written by Doyle in 2014, A Deeper Look at Uber’s Dynamic Pricing Model, Uber uses the concept of Dynamic pricing model where the pricing theory is largely supply and demand based. It capitalises on the price elasticity nature of peak/low time in which customers needing to travel and drivers being available to take them there.

As explained by Iacobucci (2013, p. 107), supply and demand follows the curve relationship where demand for sales for a particular product/service will fall when prices are set to high. Setting a price lower indeed increase sales, however too low will lose opportunity for profits.

Let’s say we take my scenario of travelling home in Sydney. From my personal experience, a normal taxi fare for would have been $15. Setting the price for $28 would not do well as customers will opt for the taxi fare instead.

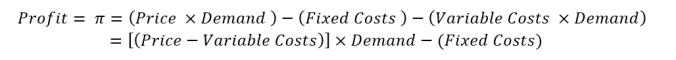

Doyle explains that Uber quickly realized in large cities on Friday and Saturday nights around 1am is the peak time where many customers want to travel home. I assume Uber’s marketers would have applied some form of profit optimisation like the following formula when deciding Uber’s fares to the customer (Iacobucci, p108).

They also applied a form of Yield management. Yield management is the process of using price and scheduling to manage demand, especially where there are limited services (Magee, p7). Friday and Saturdays at 1am is also the time that Uber divers are finishing for the day. As Uber drivers are all independent agents and a high percentage of the fares go back to the drivers, higher prices will encourage them to be rostered longer each night.

For my scenario, let’s assume there were approximately 30 cars nearby. Ignore the constant variable and fixed costs, the profit would be $15 x 30 = $450. During a festival or late night event where the number of available cars is reduced to 5, Uber’s pricing model increased this price and the fare rises to $28 with a differentiation ratio of $20/$15 = +80% markup. As a result, the profit is $28 x 5 = $140.

The change in price is known in Marketing as price elasticity. In this scenario, the demand is elastic. An elastic demand means a service is only paid a premium if the service is limited. Uber marketers have successfully followed this rule and increased the price when the demand is high with limited supply.

While this price could have easily risen to $450 / 5 = $90, with a differentiation ratio of $90/$15 = 500% markup. Uber’s marketers had intentionally not set this as the steep inflation would have had negative impacts to the customer perception of the company’s brand as a price sensible transport service that is always available.

Does Uber pricing strategy maximise profits?

Uber’s pricing model can be directly compared with other firms such as AirBnB, Taskrabbit that are growing rapidly with ‘new business modules that create lower prices, new performance parameters and new levels of scalability’ (Laurell & Sandström 2016, p 2). For example, AirBnB apartments with a view of the Mardi Gras parade increase their prices during the period and revert back to normal prices two weeks after. For these apartments with fixed supply of empty rooms, AirBnB Marketers have taken advantage of the pure demand and maximised the company’s profits.

For Uber, the company’s pricing category is targeted at the value end. It is branded to provide price competitive transport services for the customer as well as a being something profitable for the driver (Lawler, 2014). They are disadvantaged by not having fixed supply of drivers. During peak times where people want to go home, the supply for drivers is also low as drivers prefer not to be rostered at these times either. To counter this, margins have to be raised to give incentive for these drivers for driving. Uber’s Marketers had no choice but to increase these prices to maintain the supply rather than maximising their profits. Otherwise, the alternative is to have no drivers around at this time.

In closing

I hope you enjoyed reading this article. It was fascinating for me to look deeper and understand how Uber price their services based on demand. So next time when you are deciding how to get home on a busy Saturday night where there is no Taxis around, appreciate that there is a ride home and how reasonable the price is.

Posted by Justin Wong 215296673 (jgwong)

References

Goode, L 2016, Worth It? An App to Get a Cab. Retrieved on 3 September 2016, http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2011/06/17/worth-it-an-app-to-get-a-cab/

Gurley, B 2014, A Deeper Look at Uber’s Dynamic Pricing Model. Retrieved on 3 September 2016, http://abovethecrowd.com/2014/03/11/a-deeper-look-at-ubers-dynamic-pricing-model/

Iacobucci, D 2013, MM4 Marketing Management, 6th Edition, Cengage Learning, Mason USA.

Laurell, C; Sandström, C. 2016, ‘Analysing Uber in social media — disruptive technology or institutional disruption?’, International Journal of Innovation Management, June 2016 Vol. 20 No. 05.

Lawler, R 2014, Uber Slashes UberX Fares In 16 Markets To Make It The Cheapest Car Service Available Anywhere. Retrieved 5 September 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2014/01/09/big-uberx-price-cuts/

Magee, JL 1998, Yield Management : The Leadership Alternative For Performance And Net Profit Improvement, n.p.: Boca Raton : St. Lucie Press, c1998., DEAKIN UNIV LIBRARY’s Catalog, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 September 2016.